So if you happened to play something that used profanity, chances are no one would notice. Or so went the reasoning of the soon-to-be-dismissed DJ on one of the eight college radio stations I could pick up in Junior High School.

But I'm getting ahead of myself.

Although it may be hard to believe these days, Rolling Stone magazine and the National Lampoon were once serious cultural touchstones (and considered "dangerously subversive" by mainstream society and the media).

But let me back up further.

The 60s ended with a series of enormous events, any one of which would be enough to set off pop-cultural earthquakes: astronauts walked on the moon (or on a soundstage in Arizona, depending on what you believe), Woodstock brought half a million people to a farm to listen to music in the mud, Ted Kennedy drove off a bridge into shallow water at Chappaquidick Island (simultaneously killing a female campaign worker and his chance to ever become President), Monty Python's Flying Circus premiered on British television, and the Rolling Stones hired the Hell's Angels as security for a free concert (where the Angels killed a stoned Black guy with a gun who may have been trying to make Mick Jagger's fantasy of being assassinated while onstage come true).

The 60s ended with a series of enormous events, any one of which would be enough to set off pop-cultural earthquakes: astronauts walked on the moon (or on a soundstage in Arizona, depending on what you believe), Woodstock brought half a million people to a farm to listen to music in the mud, Ted Kennedy drove off a bridge into shallow water at Chappaquidick Island (simultaneously killing a female campaign worker and his chance to ever become President), Monty Python's Flying Circus premiered on British television, and the Rolling Stones hired the Hell's Angels as security for a free concert (where the Angels killed a stoned Black guy with a gun who may have been trying to make Mick Jagger's fantasy of being assassinated while onstage come true). And also the Beatles had kind of broken up, but were keeping that fact under wraps until they could finish the Let it Be album with Phil Spector.

Paul McCartney finally spilled the beans a week before his first solo album came out when he issued an "interview" (conducted by and with himself) where he declared that the Beatles had broken up. John Lennon, who wanted to announce the breakup himself months earlier but had been talked out of it by Paul, was pissed.

Lennon and Yoko Ono went to Los Angeles and underwent "primal scream therapy" with Arthur Janov. Lennon was encouraged by the sessions to confront his past traumas and he channelled some of that energy into his first real solo album John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, a record of stark, powerful, confessional songs unlike anything that came before (or has come since).

Lennon also gave a sprawling interview to Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone where, over the course of nearly three hours, he put down George Harrison, called Paul's album "rubbish," insulted Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones, and talked openly and candidly about his past and his talent. The interview took the happy mop-top Beatles image (and even the hippy-dippy, peace-and-love psychedelia of the Beatles' later years) and tore it apart. Lennon's words are shocking in their honesty and sometimes make him seem like a huge jerk. You can hear the entire interview (unedited except for boosting Wenner's off-mike questions) here.

Around the same time, Harvard grads from the Harvard Lampoon humor magazine launched the National Lampoon. The Lampoon immediately hit a chord with the counterculture, who were desperate for comedy that spoke to them (unlike the sanitized comedy on American television, which seemed permanently stuck in the early 1950s). Sex, music, war, protest, and drugs were all fair game for the Lampoon, which took particular delight in satirizing rock stars (in all their glorious excesses).

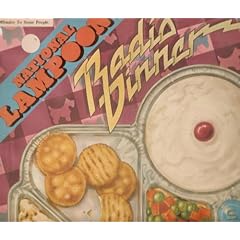

Around the same time, Harvard grads from the Harvard Lampoon humor magazine launched the National Lampoon. The Lampoon immediately hit a chord with the counterculture, who were desperate for comedy that spoke to them (unlike the sanitized comedy on American television, which seemed permanently stuck in the early 1950s). Sex, music, war, protest, and drugs were all fair game for the Lampoon, which took particular delight in satirizing rock stars (in all their glorious excesses).The National Lampoon magazine led to off-Broadway reviews, a radio show, and a handful of records featuring writers and performers like Tony Hendra, Melissa Manchester, John Belushi, Michael O'Donoghue, and Christopher Guest. The first and best of the records was National Lampoon's Radio Dinner (which has now been out of print for a shamefully long time).

All of which brings me back to Junior High. Years after the Beatles broke up (and years after Radio Dinner came out), I was listening to a college radio station late at night when the DJ decided to play a National Lampoon song that I've thought for years was called "Genius is Pain." The real title is "Magical Misery Tour" (and most of the lyrics are taken from Lennon's own words in his Rolling Stone interview).

Although I wasn't familiar with all the references, I recognized instantly how biting and funny and sad this was (and how much it must have meant to fans of the magazine, who had to be completely torn up over the Beatles breaking up).

So from that night in Junior High until today, I remembered that National Lampoon parody but had never heard it again. My used-record store searches were doomed because I was searching for the wrong song title (and probably just glossed over the title "Magical Misery Tour"). But now, thanks to the YouTube, here it is (in all it's very NSFW glory and with my added warning not to play it around young children).

Later, I learned that the DJ was kicked off the air -- not for playing a record filled with dozens of profanities (that part, apparently was fine), but because the program director didn't think the song was funny. (To be fair, the program director also didn't like Monty Python, the Rutles, and the best of early Saturday Night Live, so his judgment definitely should not be trusted.)

When Goffin's album came out, she was 19 and the critics harped on how her record wasn't as good as Carole King's Tapestry (which featured backing vocals by James Taylor and Joni Mitchell and was produced after King had nearly a decade as a hit songwriter under her belt). After a couple of other albums in the 1980s, Goffin's priorities shifted (as indicated by the photo to the right, borrowed from Goffin's MySpace page) and she got married and started a family. After 13 years away, Goffin signed with Dreamworks records and released Sometimes a Circle in 2002, which was smooth, confident, and totally out of touch with what most fans wanted.

When Goffin's album came out, she was 19 and the critics harped on how her record wasn't as good as Carole King's Tapestry (which featured backing vocals by James Taylor and Joni Mitchell and was produced after King had nearly a decade as a hit songwriter under her belt). After a couple of other albums in the 1980s, Goffin's priorities shifted (as indicated by the photo to the right, borrowed from Goffin's MySpace page) and she got married and started a family. After 13 years away, Goffin signed with Dreamworks records and released Sometimes a Circle in 2002, which was smooth, confident, and totally out of touch with what most fans wanted.

When I first heard the Bruce Springsteen song "Hungry Heart," I wasn't thinking about the great Flo & Eddie (from the Turtles) backing vocals, or Springsteen's own vocal, which was sped up slightly to add urgency to the track. I wasn't thinking about how Springsteen wrote the song for the Ramones, but his manager (who had seen the future of rock 'n' roll and its name was Bruce Springsteen) said it would be a big hit and wouldn't let the Boss give it to someone else to record.

When I first heard the Bruce Springsteen song "Hungry Heart," I wasn't thinking about the great Flo & Eddie (from the Turtles) backing vocals, or Springsteen's own vocal, which was sped up slightly to add urgency to the track. I wasn't thinking about how Springsteen wrote the song for the Ramones, but his manager (who had seen the future of rock 'n' roll and its name was Bruce Springsteen) said it would be a big hit and wouldn't let the Boss give it to someone else to record.

So that summer evening, she stood on the rocks, daring me to stop her from diving into the water. The shallow water. With the underwater obstructions and many jagged rocks. She knew what was below her. But didn’t care.

So that summer evening, she stood on the rocks, daring me to stop her from diving into the water. The shallow water. With the underwater obstructions and many jagged rocks. She knew what was below her. But didn’t care.

To hear Gina describe it, God got cranky in the mid-1970s. Rock was in bad shape and the radio was dominated by Disco, self-indulgent singer-songwriters repackaging an angst they lost four Jaguars ago, and songs by coked-up bands still coasting on a reputation they'd earned more than a decade earlier. Punk fluttered up, but acted more like a time-release drug (one that would take 15 years to fully activate).

To hear Gina describe it, God got cranky in the mid-1970s. Rock was in bad shape and the radio was dominated by Disco, self-indulgent singer-songwriters repackaging an angst they lost four Jaguars ago, and songs by coked-up bands still coasting on a reputation they'd earned more than a decade earlier. Punk fluttered up, but acted more like a time-release drug (one that would take 15 years to fully activate). For years, one of my favorite radio stations would play this song every July 4th at noon. They played it from vinyl and the record was filled with clicks and pops that perfectly amplified the song's story of disappointments and the sad shimmer of hope. A few years ago, that radio station upgraded all their equipment and their library. When they played the song at noon on the 4th of July, the sound from a shiny, newly remastered CD free from surface noises.

For years, one of my favorite radio stations would play this song every July 4th at noon. They played it from vinyl and the record was filled with clicks and pops that perfectly amplified the song's story of disappointments and the sad shimmer of hope. A few years ago, that radio station upgraded all their equipment and their library. When they played the song at noon on the 4th of July, the sound from a shiny, newly remastered CD free from surface noises.